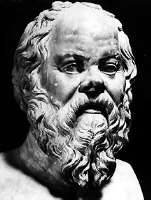

Fifth-century Athenian Socrates, set the standard for all subsequent Western philosophy.

Socrates

Socrates's conversations with his students, statesmen and friends invariably were aimed at understanding and achieving virtue {Gk. areth [aretê]}, through the careful application of a dialectical method that employs critical inquiry to undermine the plausibility of widely-held doctrines. Destroying the illusion that we already comprehend the world perfectly and honestly accepting the fact of our own ignorance, Socrates believed are vital steps towards mankind's acquistion of genuine knowledge, by discovering universal definitions of the key concepts governing human life.

Interacting with an arrogantly confident young man Euqufrwn (Euthyphro), for example, Socrates systematically refutes the superficial notion of piety (moral rectitude) as doing whatever is pleasing to the gods. Efforts to define morality, by reference to any external authority, he argued, inevitably founder in a significant logical dilemma about the origin of the good. Plato's Apologhma (Apology) is an account of Socrates's (unsuccessful) speech in his own defence before the Athenian jury; it includes a detailed description of the motives and goals of philosophical activity as he practiced it, together with a passionate declaration of its value for life. The Kritwn (Crito) reports that during Socrates's imprisonment he responded to friendly efforts to secure his escape by seriously debating whether or not it would be right for him to do so. He concludes to the contrary that an individual citizen - even when the victim of unjust treatment - can never be justified in refusing to obey the laws of the state.

Can virtue be taught? Socrates direct answer to that question is that "virtue is unteachable" however, Socrates does propose the doctrine of recollection to explain why we nevertheless are in possession of significant knowledge about such matters. Most remarkably, Socrates argues that knowledge and virtue are so closely related that no human agent ever knowingly does evil: we all invariably do what we believe to be best. Improper and Unbecoming Conduct, then can only be a product of our Ignorance rather than a Symptom of weakness of the will {Gk. akrasia [akrásia]}.

Courtesy of FIFA.com

(FIFA.com) Friday 21 January 2011

Albert Camus

The winner of the 1957 Nobel Prize for Literature, a noted goalkeeper in his youth, clearly felt the game was noble and significant. "All that I know most surely about morality and obligations I owe to football," the celebrated author wrote.

"Philosophy, says the dictionary, is the systematic and logical examination of the nature, causes, or principles of reality and knowledge. The discipline is also the source of literally thousands of fabulously quotable quotes. "I know nothing except the fact of my ignorance," declared Socrates. "The journey is the reward," intoned the ancient Chinese. These are concepts you could easily debate long into the night, or ponder from every angle over a period of months or even years.

And there we have a powerful similarity with football, another subject prone to ceaseless debate, a vast range of opinions, and contemplation of the mysteries of life. Unsurprisingly, some of history’s greatest thinkers have also turned their considerable intellectual powers to the world’s favourite game. In our brief, light-hearted and necessarily eclectic selection of philosophers’ musings about the beautiful game, let’s make a start with the dramatist, sage and poet William Shakespeare.

You can’t please them allOne of the Bard’s contemporaries, Richard Mulcaster, was an early supporter of the embryonic sport. In 1581, the headmaster of Merchant Taylors’ School wrote that "footeball… strengtheneth and brawneth the whole body, and by provoking superfluities downward, it dischargeth the head, and upper parts." Shakespeare, however, appears to have been less convinced.

In The Comedy of Errors, first performed in the early 1590s, Dromio of Ephesus responds thus to a beating from his mistress Adriana: "Am I so round with you as you with me, That like a football you do spurn me thus? You spurn me hence, and he will spurn me hither: If I last in this service, you must case me in leather." A decade or so later, Shakespeare had King Lear voicing approval when Kent sends Oswald packing with the words: "You base football player."

Fast-forward a few centuries, and we find Albert Camus adopting an entirely different stance. The winner of the 1957 Nobel Prize for Literature, a noted goalkeeper in his youth, clearly felt the game was noble and significant. "All that I know most surely about morality and obligations I owe to football," the celebrated author wrote.

Since the dawn of timeOther sages have reflected on the timelessness of it all. "Hundreds of thousands of years ago, mankind delighted in setting objects rapidly in motion by kicking them. However, we were still walking on four legs at the time, so any shot at goal generally became tangled up in the front legs," quipped German humorist Vicco von Bulow, better known by his nom de plume of Loriot.

For a rather more scientific approach, we turn to another German, Horst Bredekamp: "There is no other field in which such elementary yet highly differentiated processes are set in motion by such simple methods in such a small space. Football is the world’s theatre," the art historian noted. Bob Marley’s philosophy was rather more simply put, but even grander in scope. "Football is freedom, a whole universe. Me love it because you have to be skilful to play it," the reggae icon said.

Praying for a winStaying with the musical theme, Swedish country-dance band Rednex once sang "Football Is Our Religion", and many fine minds have pondered long and hard on the quasi-religious dimension to the game, and the shared features such as worship, fervour, and strict codes of conduct.

"How is soccer like God?" asked Uruguayan journalist, writer and novelist Eduardo Galeano, before answering his own question: "Each inspires devotion among believers, and distrust among intellectuals." No less a figure than Italian sage Umberto Eco has a characteristically strong opinion too: "Football is one of the most popular religious superstition nowadays. It is the true opium of the people today."

Art for art’s sake

Others detect a more positive cultural influence. “Football creates a democratic basis for exchange, a genuine cultural dialogue," said prize-winning Cameroonian author Calixthe Beyala. "For a footballer, football is a sport (and a job and a business), but for non-players, i.e. for all other people, football is art, the art of living,” declared Austrian writer Egyd Gstättner.

Others detect a more positive cultural influence. “Football creates a democratic basis for exchange, a genuine cultural dialogue," said prize-winning Cameroonian author Calixthe Beyala. "For a footballer, football is a sport (and a job and a business), but for non-players, i.e. for all other people, football is art, the art of living,” declared Austrian writer Egyd Gstättner.

French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, a leading figure in mid-20th century art and politics, also turned his formidable thought processes to the sport, exploring the depths and complexities of the game in the minutest detail before coming to the pithy but undeniable conclusion: "In football, everything is complicated by the presence of the other team."

Gary and Sepp, united by philosophyThat piece of deduction holds particularly true if you happen to be England and the ‘other team’ happens to be Germany. Gary Lineker may not rank alongside Sartre as a novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer or literary critic, but he scored some cracking goals and came out with one of the most often-quoted lines of modern times: "Football is a simple game. Twenty-two men chase a ball for 90 minutes, and at the end the Germans win."

And speaking of the Germans, we cannot end our sally down the highways and byways of erudite reflection on football without a nod to Sepp Herberger, architect of his country’s epoch-making 1954 FIFA World Cup™ triumph and one of the all-time greats when it came to terse but timeless comments on the game and the greater meaning of life. "After the match is before the match," "The ball is round," and "A match lasts 90 minutes," said The Chief. It's hard to imagine Confucius himself doing much better than that".

In conclusion, Incontinent agents suffer from a sort of weakness of the will {Gk. akrasia [akrásia]} that prevents them from carrying out actions in conformity with what they have reasoned. (Nic. Ethics VII 1) This may appear to be a simple failure of intelligence, Aristotle acknowledged, since the akratic individual seems not to draw the appropriate connection between the general moral rule and the particular case to which it applies. Somehow, the overwhelming prospect of some great pleasure seems to obscure one's perception of what is truly good. But this difficulty, Aristotle held, need not be fatal to the achievement of virtue.

Although incontinence is not heroically moral, neither is it truly vicious. Consider the difference between an incontinent person, who knows what is right and aims for it but is sometimes overcome by pleasure, and an intemperate person, who purposefully seeks excessive pleasure. Aristotle argued that the vice of intemperance is incurable because it destroys the principle of the related virtue, while incontinence is curable because respect for virtue remains. (Nic. Ethics VII 8) A clumsy archer may get better with practice, while a skilled archer who chooses not to aim for the target will not.Siena doth 'Protest',

Kiaora kia koutou katoa.

Thank you All and Sundry.

No comments:

Post a Comment